Contents

Legislative framework and structure of education administration

The legislative framework governing and guiding the Spanish education system consists of the 1978 Spanish Constitution and the statutes implementing the principles and rights set out therein: the Statute Law on Right to Education 1985 (Ley Orgánica 8/1985), the Statute Law on Vocational Training and Qualifications (Ley Orgánica 5/2002), the Statute Law on Education (Ley Orgánica 2/2006) and the Statue Law on Education Standards Improvement (Ley Orgánica 8/2013).

Since the approval of the Spanish Constitution in 1978, the Spanish education system has undergone a process of change in which Central Government has gradually transferred functions, services and resources to the autonomous communities. Between 1981 and 2000, the functions, services and resources of both university and non-university education were adopted by all autonomous communities.

Fachada del Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte)This decentralized model distributes powers between the State, autonomous communities and educational institutions. The State has retained exclusive powers in ensuring the unity, homogeneity and guarantee of the basic conditions of equality in the exercise of fundamental educational rights, as set out in the Constitution. For the most part, these are regulatory powers governing basic aspects of the system, although some are more executive in nature.

The autonomous communities have powers to draft regulations implementing State legislation and governing non-core aspects, together with executive and administrative powers to manage the system in their region, with the exception of powers reserved for the State.

The legislation does not afford the status of education authority to local authorities but it does recognize the possibility of their working with the State and regional authorities on the development of education policy.

The Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport is the Central Government body responsible for proposing and implementing government guidelines on education policy. Central Government has an Education Inspectorate (alta inspección educativa) in each autonomous community, charged with the exercise of government functions in this area. These functions include verifying compliance with regulations and the basic conditions guaranteeing equality for all Spaniards in the exercise of their rights and duties in relation to education, the inclusion of core content in the curricula of the autonomous communities, and compliance with State requirements and the conditions for awarding qualifications. The Ministry acts as the education authority in Ceuta and Melilla and in institutions located abroad.

Given the division of powers between the different levels - particularly State and regional - coordination is required between the educational authorities to ensure the proper performance of certain functions. The bodies responsible for administrative coordination are the Education Sector Conference and the General Conference for University Policy, composed of the regional education ministers of the autonomous communities and the Minister of Education, Culture and Sports. They act in an advisory capacity and attached to them are lower level bodies such as the General Education Committee and sector committees: staff, vocational training colleges, etc.

Participation of the education community

The Spanish Constitution provides that the public authorities shall guarantee participation in general education planning.

Niños en el aula (Francisco Javier Martínez Adrados , Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas)Within the various levels of education management, including the learning institutions themselves, there are diverse bodies whose aim is to ensure the participation of all sectors of the educational community. At State level, this body is the State Board of Education (Consejo Escolar del Estado); across the country, Boards of Education are set up at regional, provincial, district, municipal and autonomous community level. Lastly, non-university education establishments have an Institutional Board of Education, or a Social Council if they are Integrated Vocational Training Institutions, while universities have a University Social Council.

Niños en el aula (Francisco Javier Martínez Adrados , Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas)Within the various levels of education management, including the learning institutions themselves, there are diverse bodies whose aim is to ensure the participation of all sectors of the educational community. At State level, this body is the State Board of Education (Consejo Escolar del Estado); across the country, Boards of Education are set up at regional, provincial, district, municipal and autonomous community level. Lastly, non-university education establishments have an Institutional Board of Education, or a Social Council if they are Integrated Vocational Training Institutions, while universities have a University Social Council.

A number of State bodies also participate in institutions in an advisory capacity: the General Vocational Training Board (Consejo General de la Formación Profesional), the Arts Education Council (Consejo Superior de Enseñanzas Artísticas) and the Universities Council (Consejo de Universidades).

The State Board of Education is a national body set up to ensure social participation in the general planning of education and offers advice on parliamentary bills and regulations to be presented or issued by the Government. The Board represents all social sectors involved in teaching, acting in an advisory capacity. The Universities Council has the functions of academic planning, coordination, consultation and proposals relating to university studies.

Current context and recent measures

Within the system of distributed powers over education matters, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport is responsible for implementing EU-driven reforms. The framework of reference for reforms in this area is established by the EU Europa 2020 initiative, which sets ambitious targets on improving education, especially for the population aged between 18 and 24 who have not completed higher secondary education.

The Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport has made the following diagnosis of the situation in the Spanish education system:

- The number of students per teacher is lower than the OECD average (for example, in the second stage of secondary education this figure stands at 11 in Spain compared with 13.3 in the OECD and 12 in the EU21) (Education at a Glance 2015 Indicator D2.2).

- Spending per pupil as a percentage of per capita GDP is similar in Spain to the figures posted by the OECD and the EU21. In terms of the resources allocated by each country according to their level of wealth, Spain posted a total spending figure in 2012 per pupil at education centres (public, private and privately-owned State-funded schools) of 27.6% of GDP per inhabitant, in line with the international averages posted by the OECD (27.4%) and the EU21 (27.7%). (Education at a Glance 2015 Indicator B1.4).

- The school drop-out rate fell significantly between 2011 and 2015. According to the Labour Force Survey conducted by the National Statistics Institute (Spanish acronym: INE), it fell from 26.5% in 2011 to 20.3% in the third quarter of 2016. This is a reduction of over six points in four years.

- In 2012, the graduation rate of young people studying Formación Profesional de Grado Medio [Intermediate Level Vocational Training] and other vocational programmes was just 33.3%, whereas the OECD average was 39.7% and the EU average was 46.1%.

- The 2013 Labour Force Survey puts the youth unemployment rate (population under 25) at 55.5%, one of the highest in the European Union. This rate is only surpassed by Greece at 58.3%, while the average for the EU28 stands at 23.6%. Nonetheless, a downward trend is now evident as the 2014 Labour Force Survey puts this rate at 51.8%. In turn, the unemployment rate among the population aged between 25 and 34 fell by 2.3 points in 2014, from 29.1% to 26.8%.

- The population aged between 15 and 29 who neither study nor work stood at 25.8% in the first quarter of 2014. It should be noted that the method used by the OECD only considers the first quarter of 2014 for this calculation. On the other hand, the statistics prepared by the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport not only consider the first quarter but the entire year 2014, and the result is very different: the percentage of young people aged between 15 and 29 who neither study nor work fell to 20.7% in 2014, which represents a decrease of 1.7 points from 22.5% in 2013.

- In all international tests sat by Spanish citizens to 2013 (PISA, TIMSS, PIRLS and PIAAC), the results are below the OECD average and have only improved slightly in recent years, in spite of increased investment and legal reforms.

- The results in mathematics for PISA 2012 show that educational equity results had declined in the period 2003-2012: students at a socio-economic advantage obtained +34 points (6 points more than in 2003) and, by gender, boys obtained +16 points (7 points more than in 2003).

- The biggest difference in results between autonomous regions was 55 points in 2012, equivalent to a year and a half of schooling. Of the performance differences in mathematics, 85% can be explained by socio-economic disparities.

- The data obtained from the OECD study Education at a Glance 2015 indicate that, in 2014, the percentage of the adult population in Spain holding a tertiary education qualification or higher stands at 34.7%, slightly higher than the OECD average (33.6%) and three points above the EU average. Spain has already reached the Europe 2020 Strategy target of having 40% of young people aged between 30 and 34 with a tertiary education qualification. This figure in Spain stood at 42.3% in 2014, while in the European Union it stood at 37.9%.

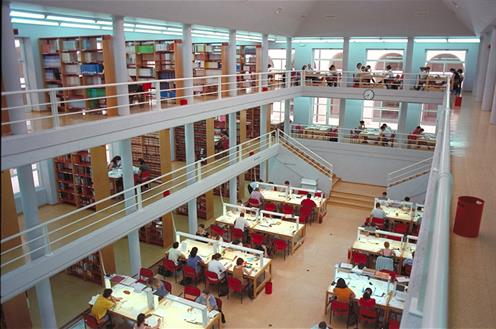

Biblioteca de la Facultad de Derecho (Universidad de Alcalá de Henares)Constitutional Law 8/2013, of 9 December, on Improving Education Quality was approved to tackle the problems identified by the afore-mentioned situation diagnosis.

Biblioteca de la Facultad de Derecho (Universidad de Alcalá de Henares)Constitutional Law 8/2013, of 9 December, on Improving Education Quality was approved to tackle the problems identified by the afore-mentioned situation diagnosis.

The general aims of this law include reducing the school dropout rate, modernising vocational training, reducing the dispersion of requirements and demands of the education system throughout the country while respecting the powers of the autonomous regions, increasing academic results in compulsory secondary education, improving academic standards in priority areas (reading comprehension, mathematical competence and scientific competence), and setting up a clear system marking the objectives met at the end of each stage.

The key measures adopted include:

- Tailored support and more flexible trajectories: students may now choose their educational trajectories as from the third year of compulsory secondary education. The law also develops alternative routes and complementary support mechanisms for students and sets up tailored attention measures.

- Modernisation of vocational training: access between different vocational training cycles is made more flexible. Dual vocational training is regulated in an attempt to facilitate access to jobs, forge links and co-responsibility with businesses, promote faculty relations with companies in the sector, and obtain qualitative and quantitative information on which to base decision making regarding the vocational training system and the courses offered.

- New syllabus configuration: one of the cornerstones of the reform concerns the new configuration of the syllabus for the Primary Education, Compulsory Secondary Education and Higher Secondary Education (Bachillerato) systems. It guarantees a minimum study workload - and the minimum content thereof - and the assessment criteria and assessable learning standards in those subjects that must be common for all students, which are included in the block of core subjects. The block of specific subjects gives students greater autonomy for setting timetables and course content, as well as for composing their course of study. There is a block of subjects that can be freely configured by the autonomous regions. This is the area where they are afforded the greatest freedom, since educational authorities and, where appropriate, schools can offer courses of their own design. The Royal Decrees on the syllabus for primary, secondary and higher secondary education have already been approved (Official State Gazettes of 1 March 2014 and 3 January 2015). Furthermore, basic Vocational Training and dual Vocational Training systems have been launched.

- Standardised assessments: the findings of the 2012 PISA report suggest that countries using external standards-based examinations tend to achieve better performances. The Constitutional Law on Improving Education Quality hence provides for a clear system marking the objectives met at the end of each stage.

- Autonomy of educational institutions: schools and colleges are given more flexibility and responsibility when it comes to choosing specialised content. Greater importance is also attached to the figure of the head teacher or director. In return for this autonomy, schools will be held accountable to society for their actions and the resources used in the development of their autonomy.

- Change in methodology: new approaches in learning and assessment focusing on the development of key skills are proposed, with special attention being paid to linguistic communication skills and STEM competencies (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), which are considered priorities for student development and their ability to navigate the world of knowledge and technology.

General structure of the education system

The Statute Law on Education Standards Improvement (Ley Orgánica 8/2013) allows students more flexibility when it comes to choosing from the different education pathways and proposes measures for switching between different teaching levels. The logic behind the education reform is based on the evolution of a system capable of channelling students towards the most appropriate pathways for their skills. The law opens gateways between and within all training pathways so that the decisions made by students are never irreversible.

Early Chilhood Education

Early childhood education is the first level of the education system and covers from birth up to the age of six years. It is organized into two three-year teaching cycles and is voluntary.

Alumnos de Educación Infantil (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte)The second cycle is free of charge. The education authorities ensure that sufficient places are offered at public schools and conclude agreements with private schools, within the context of their education programmes. The Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, in collaboration with the autonomous communities, has made a concerted effort in recent years to increase enrolment rates in the first cycle (from birth to age three) with the creation of new nursery schools following the launch of the Plan to Promote Childhood Education from 0-3 (Plan de Impulso de Educación Infantil 0-3), known as Plan Educa3.

Alumnos de Educación Infantil (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte)The second cycle is free of charge. The education authorities ensure that sufficient places are offered at public schools and conclude agreements with private schools, within the context of their education programmes. The Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, in collaboration with the autonomous communities, has made a concerted effort in recent years to increase enrolment rates in the first cycle (from birth to age three) with the creation of new nursery schools following the launch of the Plan to Promote Childhood Education from 0-3 (Plan de Impulso de Educación Infantil 0-3), known as Plan Educa3.

Both cycles promote children's physical, intellectual, emotional and social development, seeking to assist them in the discovery of the physical and social characteristics of the environment in which they live and helping them to develop a positive and balanced self-image while gaining more personal autonomy.

The education authorities are responsible for introducing children to foreign languages, literacy, basic numeracy, information technology, and visual and musical expression in the second cycle.

Primary Education

This educational stage is mandatory and, in conjunction with compulsory secondary education (ESO), constitutes the period of free, basic education. Its purpose is to facilitate the learning of speaking, listening, reading and writing skills, numeracy, basic notions of culture and the habits of co-existence, work and study, an artistic sense, creativity and affectivity to ensure a comprehensive education for the child that will contribute to the full development of his/her personality. Primary education comprises six academic courses and pupils are usually between the ages of six and twelve years.

En el curso 2014-2015, se han implantado los cursos 1º,3º y 5º y en el curso 2015-2016, se han implantado los cursos 2º,4º y 6º, con lo que la Educación Primaria quedará totalmente implantada al finalizar este curso.

Secondary Education

Compulsory secondary education (Educación Secundaria Obligatoria or "ESO") is usually studied between the ages of twelve and sixteen years, and comprises four academic courses. The ESO stage is organized into subjects and comprises two cycles, the first of which lasts for three school years and the second for just one.

Students choose either the academic subjects pathway, geared towards the bachillerato, or the applied learning pathway, in preparation for intermediate-level vocational training.

At the end of the fourth course, a personal assessment is made for either the academic subjects or applied learning option. This assessment checks whether the objectives of the stage have been reached and the degree of acquisition of the relevant skills. Students may sit the test for one or both options, regardless of the option studied in the fourth year of their compulsory secondary education.

Alumnos (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte)The Statute Law on Education Standards Improvement provides for Learning and Performance Improvement Programmes of a two-year duration. As of the second course of compulsory secondary education, a specific methodology will be used through organized content, practical activities and, where appropriate, subjects other than those of the general option, allowing students to take the fourth course through the ordinary route and obtain a certificate of completion of their compulsory secondary education.

Alumnos (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte)The Statute Law on Education Standards Improvement provides for Learning and Performance Improvement Programmes of a two-year duration. As of the second course of compulsory secondary education, a specific methodology will be used through organized content, practical activities and, where appropriate, subjects other than those of the general option, allowing students to take the fourth course through the ordinary route and obtain a certificate of completion of their compulsory secondary education.

The purpose of compulsory secondary education is to prepare students for further study or the labour market, as well as to train them in the exercise of their rights and duties as citizens.

Years 1 and 3 will be implemented in the 2015-2016 academic year, while Years 2 and 4 will be implemented in the 2016-2017 academic year.

The final assessment of compulsory secondary education corresponding to the exams sat in 2017 will have no academic effects. Only one set of exams will be sat in that academic year.

Bachillerato

The Bachillerato (Higher Secondary Education Qualification) is a two-year period of non-compulsory education that can be studied under one of three different categories: "Sciences", "Humanities and Social Sciences" and "Arts". The aim of higher secondary education is to provide pupils with the training, intellectual and human maturity, knowledge and skills required to undertake social functions and enter the labour market with an appropriate degree of responsibility and skills. It also prepares pupils to enter higher education.

The Bachillerato is open to those pupils who have obtained a Qualification of Compulsory Secondary Education [Spanish acronym: ESO] through academic study. Pupils start studying the Bachillerato at the age of 16 and finish at the age of 18, although it is possible to continue studying the Bachillerato under the ordinary regime for a maximum of four years. The Bachillerato prepares pupils to enter higher education.

An individualised exam must be taken upon completing the Bachillerato that assesses pupils regarding the degree to which they have reached the targets set for this period of education and their acquisition of the corresponding skills. Successfully passing this final is a necessary requirement for obtaining the title of Bachiller (Holder of a Higher Secondary Education Qualification).

Year 1 will be implemented in the 2015-2016 academic year, while Year 2 will be implemented in the 2016-2017 academic year.

The first final assessment of higher secondary education will be sat in the 2016-2017 academic year by those pupils studying Year 2 of Higher Secondary Education and will have no academic effects (it will not be necessary to pass this assessment to obtain the Certificate of Higher Secondary Education). However, it will be taken into consideration for access to university and for issuing the Certificate of Higher Secondary Education to pupils who currently hold an intermediate or higher technical qualification in Vocational Training or Professional Music or Dance Studies.

The final assessment will be sat at the end of the 2017-2018 academic year and will have academic effects.

Vocational Training

Vocational training covers a series of training activities designed to equip students with the skills to enter diverse professions and gain access to jobs. Students may switch between vocational training and other education pathways.

Vocational training is organised into basic, basic professional training, intermediate and advanced training cycles. All of them comprise theoretical-practical modules of varying duration, include one work placement module and can be offered in a campus-based or distance-learning-based format, or a combination of both. After first consulting with the regional governments, the Government of Spain establishes the range of qualifications corresponding to vocational training programmes, as well as the basic curriculum components of each one.

The Basic Professional Training cycles represent a new training course for pupils of compulsory secondary education. It is offered in those cases where it is considered the best option for continuing their studies or joining the labour market. These courses are accessed after completing the first cycle of Compulsory Secondary Education and following a proposal from the faculty at the centre based on skill acquisition performance. Once all modules have been passed, a Basic Professional qualification corresponding to the pertinent profession is issued to the pupil. This qualification grants access to intermediate-level vocational training studies, as well as the chance to obtain a Compulsory Secondary Education Graduate certificate.

Generally-speaking, the Compulsory Secondary Education Graduate certificate is needed to access intermediate-level training cycles. However, other access routes are available. Once all modules have been passed, a Professional qualification corresponding to the pertinent profession is issued to the pupil. This qualification grants access to advanced-level professional training studies after passing an admissions process.

Generally-speaking, a Certificate of Higher Secondary Education is needed to study advanced training cycles, including non-university higher education. However, other access routes are available. Once all courses comprising the cycle have been passed, an Advanced Professional qualification corresponding to the pertinent profession is issued to the pupil. This qualification grants access to university studies.

Dual Vocational Training, currently in the project development stage, aims to standardise the teaching and learning process at both education centres and on work placements in order to ensure that the education provided meets the needs of business. The Government of Spain will regulate the conditions and basic requirements that allow its implementation by education authorities.

Artistic Studies

The purpose of arts education is to provide quality training in the arts and guarantee the qualification of future professionals in the various fields of art.

It comprises the following studies: elementary music and dance studies, professional artistic music studies, dance studies and intermediate- and advanced-level training cycles in the visual arts and design and higher art studies.

Higher art studies comprise advanced studies in Music and Dance, Dramatic Art studies, the Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Assets, advanced studies in Design and advanced studies in the Visual Arts, which include advanced studies in Ceramics and advanced studies in Glass. Access to these advanced study courses requires a Certificate of Higher Secondary Education and an access exam to be passed. These higher art studies lead to Advanced Qualifications that, for all effects and purposes, are included in Level 2 of the Spanish Qualifications Framework for Higher Education and are equivalent to a university degree.

The portfolio of post-graduate studies comprises the official qualifications of Master of Art, which for all effects and purposes are equivalent to a post-graduate university qualification.

Language Learning

The purpose of special foreign language education is to equip pupils with the skills necessary for the appropriate use of different languages, outside the ordinary education system and is organized into basic, intermediate and advanced levels. These correspond to levels A, B and C, respectively, of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, which are subdivided into the levels A1, A2, B1, B2, C1 and C2.

Pupils must be 16 years of age in the year they begin study to access this education. Pupils over the age of 14 may also be admitted to study a foreign language not provided as part of their compulsory secondary education curriculum.

After consulting with the regional governments, the Government of Spain will determine the degree of equivalence between the special foreign language education qualifications and other qualifications comprising the education system.

Sports Education

The purpose of sports education is to prepare pupils for a profession in a specific field or area of sport, to facilitate their adaptation to changes in the labour market and sports world, and to encourage active citizenship.

This is organised around the various fields and, as appropriate, specialities of sport. It comprises two levels - an intermediate level and an advanced level - and may relate to the National List of Professional Qualifications. This is organised in blocks and modules of varying duration, and consists of theoretical and practical subjects related to the various professional fields and sports.

Those who pass intermediate-level sports education will receive a Sports Professional qualification in the corresponding sports category or speciality. Those who pass advanced-level sports education will receive an Advanced Sports Professional qualification in the corresponding sports category or speciality. The Sports Professional qualification will grant access to all areas of Higher Secondary Education. The Advanced Sports Professional qualification will grant access to degree-level university studies after completing an admissions procedure.

Higher Education and access

The general requirement for university entrance under the Statute Law on Education Standards Improvement is the Bachillerato qualification, which includes the grades obtained for both years and requires passing the final exam to assess the student's academic maturity, knowledge and ability to pursue university studies successfully. Universities may also establish an admissions procedure in accordance with Government regulations.

The aforementioned Royal Decree also regulates direct university access for students of advanced-level vocational training, Visual Arts and Design and Sports Studies, and the examination for students aged over twenty-five years, university access for the over-40s through the accreditation of work experience and access for the over-45s with no academic qualifications or professional experience, thereby guaranteeing adult access to education.

The Statute Law on Education Standards Improvement also makes university entry requirements more flexible for foreign students holding a qualification or diploma equivalent to the Bachillerato and will come into force during the 2014-2015 academic year.

This entrance system is expected to be maintained during the 2017-2018 academic year, in which the system introduced by the Statute Law on Education Standards Improvement will come into force and the entrance test will be replaced by an admissions procedure in accordance with the basic Government regulation.

The university system

Elements of the System

Constitutional Law 4/2007, of 12 April, amending Constitutional Law 6/2001, of 21 December, on Universities introduces a series of reforms to promote the autonomy of universities as recognised in the Spanish Constitution while increasing their accountability for how they perform their functions. These changes were specifically aimed at improving the quality of Spanish universities and to ensure their trouble-free incorporation into the framework of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) and the incorporation of Spanish academic research into the European Research Area project.

Rectorado de la Universidad de Alcalá (Universidad de Alcalá de Henares)There are 83 universities in Spain in the 2014-2015 academic year, of which 50 are public and 33 are private. There are currently 345 university campuses located in various towns and cities around the country. These figures show that universities and their campuses are scattered around Spain. As regards the courses on offer, it should be said that 2,635 university degrees and 4,087 official master's courses were confirmed in 2014. During the 2014-2015 academic year, the number of students enrolled on first and second cycle undergraduate courses in the university system stood at approximately 1,412,673, while the number of students on master's courses stood at 120,055. This brings the number of students enrolled in the university system up to 1,532,728 students, not including students enrolled on doctorate programmes.

Rectorado de la Universidad de Alcalá (Universidad de Alcalá de Henares)There are 83 universities in Spain in the 2014-2015 academic year, of which 50 are public and 33 are private. There are currently 345 university campuses located in various towns and cities around the country. These figures show that universities and their campuses are scattered around Spain. As regards the courses on offer, it should be said that 2,635 university degrees and 4,087 official master's courses were confirmed in 2014. During the 2014-2015 academic year, the number of students enrolled on first and second cycle undergraduate courses in the university system stood at approximately 1,412,673, while the number of students on master's courses stood at 120,055. This brings the number of students enrolled in the university system up to 1,532,728 students, not including students enrolled on doctorate programmes.

There are 84 universities in Spain in the 2015-2016 academic year, of which 50 are public and 34 are private. There are currently 352 university campuses located in various towns and cities around the country. These figures show that universities and their campuses are scattered around Spain. As regards the courses on offer, it should be said that 2,725 university degrees and 4,315 official master's courses were on offer in 2015.

Competitiveness of the Spanish University System

The modernisation of Spanish universities, a necessary step for their integration into and adaptation to the European Higher Education Area, began with the intergovernmental agreement known as the Bologna Declaration, signed on 19 June 1999, which set out the commitment to "harmonise higher education in Europe and foster collaboration between the different Member States and universities in order to establish a system of recognised qualifications that enhances the mobility of students and teachers in order to boost employment and competitiveness". The date for adapting to the syllabus reform in the three cycles (bachelor's, master's and doctorate) was scheduled for the 2010-2011 academic year, although, being the dynamic process that it is, completion is ongoing.

During this period, Spanish universities have made and continue to make important changes. These modernisation changes have not been limited to adapting university degrees to the new structure; on the contrary, they have required major reforms.

Since 2011, special emphasis has been placed on measures affecting the organisation of university education and increasing mobility between universities. This was made possible only by the implementation of comparable qualifications within the European space (bachelor's, master's and doctorate).

The modernising of universities to create a more competitive Europe requires modelling the areas of action on the "Triple Helix" (business, university, government) with a basic structure framed by the "triangle of knowledge" (education, research and innovation).

Against this backdrop, the following royal decrees were approved in the field of university education in 2014:

- Royal Decree 967/2014, of 21 November, establishing the requirements and procedure for the official recognition and declaration of equivalence at a qualification and official university academic level and for the official recognition of qualifications from overseas higher education studies, and the procedure for determining the correlation to levels within the Spanish framework of qualifications for higher education of the official titles of Architect, Engineer, Bachelor (5 years), Technical Architect, Technical Engineer and Bachelor (3 years).

- Royal Decree 412/2014, of 6 June, establishing the basic regulations governing admission procedures to official university education at a degree level.

- Royal Decree 43/2015, of 2 February, amending Royal Decree 1393/2007, of 29 October, establishing the structure of official university education and Royal Decree 99/2011, of 28 January, governing official education at a doctorate level.

- Royal Decree 22/2015, of 23 January, establishing the issuance requirements for the European Supplement to qualifications governed by Royal Decree 1393/2007, of 29 October, establishing the structure of official university education and amending Royal Decree 1027/2011, of 15 July, establishing the Spanish Framework of Qualifications for Higher Education.

The following royal decrees were approved in the field of university education in 2015:

- Royal Decree 22/2015, of 23 January, establishing the issuance requirements for the European Supplement to qualifications governed by Royal Decree 1393/2007, of 29 October, establishing the structure of official university education and amending Royal Decree 1027/2011, of 15 July, establishing the Spanish Qualifications Framework for Higher Education.

- Royal Decree 43/2015, of 2 February, amending Royal Decree 1393/2007, of 29 October, establishing the structure of official university education and Royal Decree 99/2011, of 28 January, governing official education at a doctorate level.

- Royal Decree 415/2015, of 29 May, amending Royal Decree 1312/2007, of 5 October, establishing the national accreditation for access to university faculties.

- Royal Decree 420/2015, of 29 May, on the creation, recognition, authorisation and accreditation of universities and university centres.

Furthermore, the Task Force for the Internationalisation of Universities was set up in July 2013 with a view to following the recommendation contained in the Bucharest Ministerial Communiqué from the Education Ministers from the European Higher Education Area regarding the need for all EHEA countries to develop national internationalisation strategies with specific targets and measures and quantifiable indicators.

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte)The strategy developed is based on a broader concept of internationalisation that goes beyond student mobility and the signing of international agreements, on which work continues to be done and a system of objectives and lines of action is proposed with a view to establishing a highly internationalised university system, increasing the international appeal of universities, fostering the international competitiveness of the environment and intensifying cooperation with other actions around the world.

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte)The strategy developed is based on a broader concept of internationalisation that goes beyond student mobility and the signing of international agreements, on which work continues to be done and a system of objectives and lines of action is proposed with a view to establishing a highly internationalised university system, increasing the international appeal of universities, fostering the international competitiveness of the environment and intensifying cooperation with other actions around the world.

In line with the search for university system competitiveness and, stemming from the commitment made by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport to employability in the offer from Spanish universities, significant work has been carried out to complete the Integrated University Information System of the ministerial department with employability data in order to provide information on the insertion into the labour market of university graduates.

Through this far-reaching and ambitious study, the Government of Spain is providing the public, the public authorities and the education community with the information needed to enable a clear diagnosis of the current situation for the purpose of adequately planning its university policies and the lines of action to be followed. Furthermore, students - as the direct recipients of higher education - will be able to access consolidated data on the employability of the qualifications they wish to obtain.

In short, the study will make a positive contribution to creating a more efficient and balanced university system, adapting student preferences and labour market needs and avoiding disconnection processes between the offer of university qualifications and the offer of employment. Achieving a balance between these two concepts - an essential condition for reducing unemployment rates and avoiding an inefficient use of public resources - cannot be done without the necessary information.

Other education initiatives

Grants Policy

In terms of grants, the amount of general grants has increased. This figure has risen from a total of 1,058,757.980 euros in 2009 to 1,413,524.000 euros in the 2015 General State Budget.

Clase de Informática (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte)The budget allocated to general grants rose by 250 million euros between 2013 and 2014. Hence, over 1.411 billion euros were allocated to grants in the 2014 budget given to the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport. This is the highest figure since records began and only surpassed by the 2015 budget, in which over 1.413,5 million euros were allocated to grants. The budget was increased again in 2016 by a further three million to a total of 1.416,5 million euros. This represents an increase of almost 25% since 2012.

Clase de Informática (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte)The budget allocated to general grants rose by 250 million euros between 2013 and 2014. Hence, over 1.411 billion euros were allocated to grants in the 2014 budget given to the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport. This is the highest figure since records began and only surpassed by the 2015 budget, in which over 1.413,5 million euros were allocated to grants. The budget was increased again in 2016 by a further three million to a total of 1.416,5 million euros. This represents an increase of almost 25% since 2012.

The income thresholds for access are maintained and a minimum grade of 5.5 is set for access to university grants and 6.5 for other grants. These issues are regulated by Royal Decree 609/2013, of 2 August, establishing the family income and wealth thresholds and amounts of study scholarships and grants for the 2013-2014 academic year. The new system consists of two parts: a core of fixed amounts, which include the amounts guaranteeing the right to education for lower-income students, an amount for accommodation for those who have to travel and exemption from public prices or enrolment grants for university students and the basic grant for non-university students and a variable amount, which is distributed for each recipient and round of grants on the basis of a means-tested formula that also takes into account the academic performance of each recipient. Enrolment fee grants have also been introduced. Funds are distributed according to a formula that considers family income and the academic performance of each recipient.