Contents

- Recent developments in the Spanish economy

- Macroeconomic stability and productivity growth

- The economy by sector

- Research, Development and Innovation

- Links

Recent developments in the Spanish economy

The starting point of the design of economic policy must be the identification and analysis of the difficulties faced by the Spanish economy. During the years of economic growth and the early years of the downturn there arose major macroeconomic imbalances - a high public deficit, high private indebtedness spurred by negative real interest rates, high external debt and loss of competitiveness. A large portion of these imbalances is explained by the buoyant growth of credit in the years leading up to 2007, by the increase in mainly property-related investment, and by the rigidities of the labour market. The high rate of investment in the years leading up to 2008 explains the strong increase in external indebtedness: in particular, the weighting of housing investment alone explains half of the external imbalance created in the years leading up to 2008.

Alongside this, certain structural features of the Spanish labour market (its dual nature and the structure of wage bargaining), in conjunction with other factors, coupled with a shortfall of competition in some markets in goods and services, worsened these imbalances in the form of a trend toward a loss of outward competitiveness.

In the early stages of the crisis, a strongly expansionary fiscal policy was adopted, so as to increase public financing requirements rapidly, up to a maximum deficit of 11.2% in 2009. In the period 2000-2007 the growth of external debt was due to a need to finance the private sector; from 2009, however, the increase chiefly stemmed from the public sector.

In 2012, Spain was facing a very difficult situation, with an economy on the brink of collapse, and with some major accumulated imbalances that had to be resolved.

The correction of these imbalances is already being reflected in hard figures. At the close of 2013, the National Statistics Institute confirmed that the recession was technically at an end and the path of economic growth had begun. This improvement has been possible thanks to the structural reforms implemented and the significant process of correcting imbalances.

While at the start of the recovery it was external demand which acted as the motor of the economy, offsetting the contraction in domestic demand, since mid-2013 private consumption and investment have driven the economy forward. According to the latest data from the National Accounts (corresponding to the close of 2014), the Spanish economy has grown for six consecutive quarters, with an upward trend, thanks largely to improved financial conditions and positive domestic demand, which in turn has been boosted by increased confidence and a recovery in the labour market. Buoyed by these factors, GDP grew by 2% year-on-year in the fourth quarter of 2014, 0.4 percentage points (p.p.) more than in the previous quarter, and the highest rate of growth since the second quarter of 2008 (2.2%).

The contribution of domestic demand to GDP growth increased in the fourth quarter of 2014 for the fourth consecutive quarter, contributing 2.7 points (2.6 points in the third quarter), while external demand reduced its negative contribution to -0.7 points, 0.3 points less than in the third quarter.

As an aggregate of the four quarters, GDP growth in 2014 as a whole is estimated at 1.4%, with domestic demand contributing 2.2 points to growth and foreign demand deducting -0.8 points.

Since the start of the current crisis, Spain has been slowly but surely reducing its economy's need to borrow. In 2011, net borrowing stood at 2.8% of GDP, but already by 2012 net lending was at 0.2%, reaching 2.1% of GDP in 2013. As a result of more buoyant domestic demand, net lending has slowed for 2014 as a whole to 0.5% of GDP and the current-account surplus fell from 1.4% of GDP in 2013 to 0.1% of GDP. In the third quarter, the current-account surplus fell from 1.5% to 0% of GDP, mainly due to the deterioration in the trade balance of non-energy goods (whose surplus fell from 2.8% of GDP in the third quarter of 2013 to 1.8% in the same quarter of 2014) and the balance of primary income (which increased its deficit from 0.7% to 1.4% of GDP in the same period). The surplus from tourism services (up from 3.3% to 3.4% of GDP) and the energy deficit (from 4% to 3.8% of GDP) performed better. The positive balance of income figures in the fourth quarter, combined with the favourable impact of lower oil prices, should guarantee a slight current-account surplus in 2014.

Starting in 2008, the Spanish economy accumulated significant economic and financial imbalances to give rise to the most serious crisis in recent democratic history, which resulted in a substantial increase in unemployment. The imbalances were mainly in the fiscal and financial areas. Furthermore, the Spanish economy needed a package of reform measures to modernise the structure of production and labour relations and introduce greater competition.

On the fiscal front, 2013 ended with a deficit of 6.3% of GDP (excluding aid to the financial system), well below the figure of 11% in 2009. The figure is particularly significant considering that the reduction occurred in the context of a recession. The deficit forecast for the close of 2014 is 5.5% of GDP. The Government is firmly committed in this regard, given that the reduction of imbalances in the public finances is one of the levers for consolidating growth.

Private debt is also being reduced substantially, although it is still at high levels, particularly in terms of debt associated with property. These levels of public and private debt are strongly dependent on external sources, as can be seen from the fact that foreign debt amounted to 161.7% of GDP in September 2014. However, in net terms, Spain's total net international investment position was -95.2% of GDP at the close of the third quarter.

After 2008, the Spanish economy only experienced a short period of weak growth in 2010, which became exhausted in mid-2011, while output fell by 0.7% in the last quarter of 2011. In 2012, the economy continued to decline, with GDP down by 2.1%. In the third quarter of 2013, the Spanish economy began its expansion, and this trend has continued to strengthen over six consecutive quarters.

However, unemployment is the worst aspect of the crisis. The unemployment of around 8% in 2007 rose to some 26% at the close of 2013. It declined steadily over 2014 to 23.7% in the fourth quarter of the year. All the Government's actions are geared to the ultimate goal of job creation.

In recent years there has been significant progress in correcting imbalances. In 2013, there was a current-account surplus of around 1% of GDP, compared with a deficit of 10% in 2007. At the same time, significant improvements in competitiveness are being made, as reflected in the recent figures on unit labour costs, which in 2012 fell by 3% and in 2013 and 2014 by 0.4%. Private-sector debt is also falling at a good pace, from 203.5% of GDP in mid-2010 to 167% in the third quarter of 2014 (using consolidated figures).

As a side-effect of the recovery, domestic demand has taken over from the foreign sector as the driver of the Spanish economy, with imports (7.7% in the fourth quarter of 2014) being stronger than exports (4.7%). In any event, the ex-post competitiveness of Spanish exports, measured by export shares, has remained above that of our EU partners, except for Germany.

Domestic demand has thus become the driving force of the Spanish economy, in particular the final consumption expenditure of households, which expanded in the fourth quarter for the fourth consecutive quarter, with rates of 1.3%, 2.3%, 2.8% and 3.4%, closing 2014 at 2.4%. Gross fixed capital formation has also grown for seven consecutive quarters, with annual growth of 12.2% in 2014, much higher than in 2013 (5.6%). This strong growth in capital goods is primarily based on recovery in order books.

The private component of domestic spending has been boosted by improved household real disposable income, favoured by job creation, as well the environment price moderation and recovery in confidence. Confidence indicators are in fact recovering pre-crisis values. The Economic Sentiment Indicator stood at 107.4 in February (1990-2014 average = 100), the highest level since March 2007; while the Consumer Confidence Indicator reached a record high in January 2015 of 99.6, very close to 100, which is indicative of positive consumer perception.

On the supply side, in 2014, there was a trend for growth in all industries except construction. The gross value added (GVA) of agriculture grew by 3.3%, that of industry by 1.5% (2.3% in manufacturing), and services by 1.6%; while construction slowed its rate of decline significantly to -1.2% (an improvement of 6.9 points on 2013).

Macroeconomic stability and productivity growth

Turning around a downturn as severe as the present one calls for adopting a comprehensive, self-consistent and ambitious economic policy strategy. One of the priorities of economic policy is fiscal consolidation, and once the financial restructuring process is complete, structural reforms affecting the operation of factor, goods and services markets will be required. Over the past two years, the Government has introduced an ambitious reform programme that has restored much of the competitiveness lost since Spain joined the euro. Spain must nonetheless carry on with these reforms to equip the economy with a more efficient and flexible structure that will foster growth and job creation.

Fiscal consolidation

Fiscal consolidation is based on measures to reduce expenditure and improve the efficiency of the taxation system. This has resulted in a substantial reduction of the public deficit from 8.9% of GDP in 2011 to 6.3% in 2013 (net of financial aid), thus fulfilling the commitment made to the European Union of a maximum deficit of 6.5% of GDP.

In two years, there has been a cut in deficit of all tiers of government of 2.6 points of GDP, representing almost 30%.

There has also been a steady decline in the structural deficit, which demonstrates the real fiscal effort made by the Spanish economy. It is notable that this adjustment has taken place under very adverse cyclical conditions, with a shrinking tax base and the consequent reduction in government revenues, as well an increase in expenditure items such as unemployment benefits and debt interest payments.

This is where a reform of the fiscal framework becomes important, in order to ensure budgetary stability, financial sustainability and transparency at all tiers of government. Of note in this respect is the launch of the Independent Fiscal Responsibility Authority (Spanish acronym: AIReF), which is responsible for ensuring compliance with the principles of budgetary stability and financial sustainability. The AIReF charter approved in 2014 regulates its structure and operating rules, procedures, reports and opinions to be issued as well as the studies that can be requested from it and institutional relations. The General State Budget for 2015 is the first in which the macro-economic forecasts on which it is based have been endorsed by the AIReF.

Also worthy of mention is the amendment of Constitutional Law 2/2012, of 27 April, on budgetary stability and financial sustainability, through Constitutional Law 9/2013, on controlling the commercial debt of the public sector, which has been implemented to ensure an appropriate average payment period for suppliers.

The two mechanisms implemented in 2012 to bolster strict compliance with the stability targets of the regional governments continued to operate in 2014: the Supplier Payment Mechanism and the Regional Liquidity Fund (Spanish acronym: FLA).

In addition, the Spanish Council of Ministers approved Royal Decree-Law 17/2014, of 26 December, on financial sustainability measures for regional governments and local authorities, and other economic measures. It also approved the submission to Parliament of the Draft Constitutional Law amending the Constitutional Law on Financing Regional Governments, of 22 September 1980, and the Law on Budgetary Stability and Financial Sustainability, of 27 December 2012.

The improvement in the markets now makes it possible to extend the coverage provided by liquidity mechanisms and reduce their cost. In these circumstances, the coverage provided by the Spanish Treasury has been extended to the entire Spanish public sector. The much wider coverage means all the needs of regional governments will be financed, the liquidity needs of local authorities will be covered for the first time and new items that can be financed will be included.

The new funding mechanisms will be open to all regional governments and local authorities and their administration will be easier and more efficient. All the mechanisms supporting the liquidity of the regional governments will be included in the Regional Government Finance Fund, while the mechanisms supporting the liquidity of local authorities will be covered by the Local Authority Finance Fund.

The mechanisms for Local Authorities, depending on their financial situation, are:

- Regulation Fund: aimed at those highly indebted and at financial risk, and those that have registered an average payment period to suppliers that is over 30 days above the maximum established by the law on late payments. Local authorities benefiting from this fund will have to meet the strictest levels of fiscal compliance.

- Economic Support Fund: aimed at those authorities that meet the budgetary stability and public debt targets, and whose average payment period to suppliers is not often more than 30 days above the maximum period established by the law on late payments.

The mechanisms for Regional Governments are:

- Finance Mechanism: For those that meet the targets for budgetary stability, public debt and average payment period to suppliers. Adherence to the mechanism need not require an adjustment plan and the autonomous regions may cover the financing of the deficit target for the year, debt maturities (including loans) and overruns of unfinanced deficits in previous years.

- Regional Liquidity Fund: Intended for the regional governments that do not meet the stability or debt targets (so they are excluded from the Finance Mechanism) but apply for inclusion, plus those who repeatedly violate the average payment period for suppliers. Its conditions are the same as above for the previous Regional Liquidity Fund.

- Social Fund: Through this, regional governments may temporarily finance their outstanding debt with local authorities up to 31 December 2014, arising from arrangements on social spending.

Each of the above funds also includes the former Financing Fund for Regional Government and Local Authority Supplier Payments, thus streamlining its organisation.

In a further effort to streamline public expenditure, in June 2013 the Commission on Public Administration Reform (Spanish acronym: CORA) published its report with more than 220 proposals which will gradually be implemented until 2015, resulting in savings estimated at more than 37 billion euros. In fact, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has issued a CORA Assessment Report including its implementation until the first quarter of 2014. It notes: "The CORA reform package is the result of a rigorous process of data collection, dialogue among practitioners and diagnosis about the weaknesses of Spain's public administration services. The reform package is substantial, evidence-based and consistent with the ongoing process of modernisation. The number of policy issues included in the CORA reform (i.e. e-government, multi-level governance relations, better regulation and budget reforms) together with parallel initiatives adopted over the last two years in areas such as budget stability, transparency or democratic regeneration, explain one of the most ambitious processes of governance reform in OECD countries."

Structural reforms

Development of the reform programme initiated in the first two years of the Government's term of office continued in 2014. The priority objective continued to be to enhance the operation of the financial sector, once the financial aid programme was successfully completed in January, given the important role the sector plays in the consolidation of growth. The ultimate aim is twofold: to restore the flow of bank credit and enhance the diversification of funding sources in order to reduce dependence of business on the banking channel.

Fábrica de coches (Ministerio de la Presidencia y para las Administraciones Territoriales)The restructuring of the financial institutions which received public aid continued in 2014 and the Management Company for Assets Arising from the Banking Sector Reorganisation (Spanish acronym: SAREB) updated its business plan in favour of more active management of its portfolio to maximise results. The Government asked the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) permission to make early repayment of 1.3 billion euros of the loan to recapitalise the Spanish banking sector, which was approved by the Board of Directors of the ESM.

The return to macro-economic stability, stabilisation of the banking sector and the regulatory reforms introduced are beginning to bring results in the form of recovering credit flows in the private sector. Of particular note is the trend in new lending in the retail sector, with cumulative annual growth in 2014 of 11.4%. By sector, new loans granted to households recorded the highest annual growth rate (18.7%) with housing loans being particularly strong. New loan transactions for under one million euros were also strong, pointing to a recovery in credit for SMEs. Cumulative growth for 2014 was 8.6%, with 14 consecutive months of increases. In the case of new loan transactions with larger companies, the figures showing positive growth in December also suggest a change in trend in this sector. The cumulative decline for the year (19%) should be interpreted as part of the continuing process of deleveraging and greater use of alternative sources of finance such as stock market issues, as well as stronger self-financing.

Against this backdrop, the Official Credit Institute (Spanish acronym: ICO) has carried out notable counter-cyclical work since the beginning of the crisis. Its role as a financing agent has increased substantially, so that the volume of loans granted in 2014 accounts for almost 12% of the stock of loans in the economy, compared with only 3.5% in 2007. Its brokerage activity reached record highs in 2014, at over 21 billion euros granted, 55% up on the previous year.

In addition to the main lines of reform, other factors have also contributed to the recovery and consolidation of growth.

Improving the institutional framework

Mercado del Borne, Barcelona (J. Tern, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente)The first steps taken to reform the Spanish financial system were to support the consolidation and strengthen the solvency of financial institutions. Once this process was concluded - successfully in view of the valuations of Spanish credit institutions in the assessment exercise conducted by the European Central Bank - the mechanisms for crisis prevention and resolution were reviewed in line with the changes made at a European level, as reflected in the Draft Law on the restructuring and resolution of credit institutions and investment services firms. The ultimate goal of this regulatory review is to reconcile the need to preserve the stability of the financial system with minimising the impact of a possible resolution of a financial institution on the public purse and, at the end of the day, on taxpayers. To this end it introduces, for example, a new scheme by which losses are absorbed by creditors. Also of note is the creation of the National Resolution Fund, financed by the banks themselves, which will, as from 2016, have to be integrated into in a single European fund. Similarly, the law introduces mechanisms for collaboration between the Spanish resolution authorities and the Single Resolution Mechanism.

Mercado del Borne, Barcelona (J. Tern, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente)The first steps taken to reform the Spanish financial system were to support the consolidation and strengthen the solvency of financial institutions. Once this process was concluded - successfully in view of the valuations of Spanish credit institutions in the assessment exercise conducted by the European Central Bank - the mechanisms for crisis prevention and resolution were reviewed in line with the changes made at a European level, as reflected in the Draft Law on the restructuring and resolution of credit institutions and investment services firms. The ultimate goal of this regulatory review is to reconcile the need to preserve the stability of the financial system with minimising the impact of a possible resolution of a financial institution on the public purse and, at the end of the day, on taxpayers. To this end it introduces, for example, a new scheme by which losses are absorbed by creditors. Also of note is the creation of the National Resolution Fund, financed by the banks themselves, which will, as from 2016, have to be integrated into in a single European fund. Similarly, the law introduces mechanisms for collaboration between the Spanish resolution authorities and the Single Resolution Mechanism.

But it is as important to have an efficient system for channelling finance to its most productive uses as it is to allow that in case of failure, the maximum value of the investment can be rescued and destined efficiently to alternative uses. It is essential that corporate restructuring mechanisms allow the continuity of companies that are ongoing concerns but are in difficulties due to excessive debt. To do so, the pre-insolvency phase has been modified by Law 17/2014, of 30 September, on restructuring and refinancing, which relaxes the conditions of refinancing agreements. The importance attached to the proper operation of the insolvency system has, in fact, led to the creation of the Monitoring Committee on Practices of Refinancing and Reduction of Excessive Debt, which is responsible for analysing the effects of the measures implemented in insolvency proceedings and implementing any other proposals that contribute to deleveraging in the private sector.

New channels for finance

Improvements in the system of insolvency proceedings should help improve the prospects for the recovery of investments made by creditors in the company in the event of its winding up. These measures will also help to expand the range of credit options available to businesses, in particular for SMEs. They complement the other actions taken to diversify sources of business finance in order to reduce the strong dependence of the Spanish productive sector on bank credit.

Along these lines, other legal amendments have been approved or are being processed over the last year. First, the approval and enactment in November of Law 22/2014, regulating venture capital institutions, other closed-investment institutions and the companies managing collective investment firms, and amending Law 35/2003 on collective investment institutions. This provision seeks to encourage a greater flow of funds to venture capital operations to enable a larger number of companies to receive finance; and also to try to channel this type of investment more to the financing of small and medium-sized enterprise in their early stages of development and expansion, as they have the greatest difficulties to access finance.

The legal change has again been bolstered by the role of the ICO. The FondICO Global fund of 1.2 billion euros, acts as a catalyst for the venture capital sector in Spain. Since it was set up a year ago, FondICO has helped create 23 new funds, with an overall target of 8.6 billion euros and an investment commitment of at least 2 billion euros in Spanish SMEs. This figure is five times the average volume of investment to the sector in the last five years. Beyond its quantitative importance, FondICO is key due to the support it provides for developing business projects, especially at their earliest stages.

In addition, the Law Promoting Corporate Finance will allow easier access by businesses to finance on the capital markets by freeing the issue of bonds by publicly listed companies and increasing the flexibility of the system of issuing bonds by limited companies. It also provides access to the stock market from the Alternative Stock Market (MAB) and revises the supervision standards by the National Securities Market Commission (CNMV) to increase investor confidence.

Second, regulation has been introduced in Spain for the recently introduced system for capturing and channelling funds known as "crowdfunding" (participatory funding platforms). This is particularly relevant for providing capital to small companies in their early stages of development, while maintaining appropriate protection for investors.

Third, funding of SMEs has been made more attractive by improving the guarantee system provided by the Spanish Rebonding Company (CERSA) and reform of the system of securitisation that seeks to revitalise this market while promoting transparency, simplicity and quality standards. However, the most original measure is the requirement in the Law for SMEs to have access to their credit ratings from credit institutions, based on a common methodology and models drawn up for this purpose by the Bank of Spain. In addition, banks will be forced to give three months' notice to the SMEs whenever they want to reduce their finance.

Improving the business climate and supporting SMEs

In addition to the actions taken in the financial sector, work has also continued on the cross-cutting reforms to improve the business environment and support SMEs, thus contributing to an improvement in the competitiveness of the Spanish economy.

The year 2014 is the first year of the application and implementation of Law 14/2013, of 27 September, supporting entrepreneurs and their internationalisation. Its provisions include the exercise of reviewing and improving the business climate to be carried out annually under the coordination of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Competition. This exercise will involve economic agents and all tiers of government with regulatory responsibilities in an ongoing task of regularly analysing and pushing through regulatory or procedural changes that make it easier to do business and create wealth.

The Doing Business in Spain study is another consequence of the implementation of this law. This study is prepared by the World Bank, and aims to identify and promote the adoption of best practices in regional and local regulation of the business environment, using an independent and consolidated methodology.

Law 20/2013, of 9 December, on guaranteeing market unity and the Market Unity Programme have also been implemented and developed in 2014. The law seeks to eliminate the fragmentation of the national market by applying the principles of non-discrimination, cooperation and mutual trust between different public authorities, necessity and proportionality in the actions of the competent authorities and simplification of administrative burdens. Of note in this respect is the collaboration between different public authorities within the framework of the Council for Market Unity and sector-based conferences (over 20 are already operating within this framework).

To comply with the Market Unity Programme, there has been work in 2014 along two lines. First, an ambitious Regulatory Streamlining Plan was launched in collaboration with the regional governments. It has already changed more than 80 national regulations and over 35 in priority economic sectors are being processed. At the same time, the regional governments have proposed more than 400 regulatory changes. In addition, since March specific procedures are in place for the protection of economic agents by which companies and associations can file complaints when they encounter barriers to their economic activity. In less than a year, more than 85 cases have already been submitted through these mechanisms, of which over 50 have been resolved, 2/3 of them in favour of the agents. The full impact of this Market Unity Programme is estimated at more than 1.5% of GDP.

Fábrica (Ministerio de la Presidencia y para las Administraciones Territoriales)Furthermore, a de-indexation policy was initiated in our economy in 2014, designed to stop the use of inefficient and distorting indexation mechanisms in public sector contracts. Along these lines, the Law on de-indexing the Spanish economy will be passed in 2015, affecting all the monetary figures in the public sector. The law aims to establish a new system that updates prices rationally and consistently with a low inflation environment. The objective is to ensure a better allocation of resources and avoid inflationary inertia, thus increasing economic competitiveness.

Finally, three actions included in the adoption and implementation of CORA measures support the creation and development of SMEs. First, the elimination of obstacles to creating new companies, which has been given a new boost by the development in 2014 of "Emprende en 3" [opening a business in 3 days]. This platform combines the efforts of the three tiers of government involved in the paperwork relating to company creation: central government, regional governments and local authorities. It is an example of administrative streamlining that focuses on the use of electronic media and the systematic use of undertakings of compliance, i.e. a posteriori control, to streamline the process of creating or transferring a business.

Second, the implementation of a centralised database on aid and finance for SMEs. This database contains the aid programmes and incentives that support businesses organised and granted by the three tiers of government. It is integrated within the National Database of Grants, which provides access to information about the programmes offering public financial support and ensure their wider dissemination, uptake and use.

Third, in the 2014 progress has been made on providing SMEs with easier access to public procurement. This was achieved through measures such as the implementation of the Platform for Public Sector Procurement, which centralises all information on bids made by any entity subject to the Law on public sector procurement.

The economy by sector

Service Sector

The Gross Value Added of the service sector in 2014 at current prices was 718.31 billion euros, accounting for 67.9% of GDP, up by 0.4 percentage points on 2013 as a whole.

In 2014, the sector employed an average of 12.7 million people, approximately 77% of total jobs. By sub-sector, trade, transportation and hotel & catering accounted for 33.2% of value-added services (with an average of 5 million jobs). Next came the civil service, defence, compulsory social security, education, healthcare and social services, accounting for 25.1% of the sector, with 3.6 million jobs.

In 2014, the nominal value added of all sub-sectors increased, except for information and communications, which fell by 3%. Artistic, recreational and other services grew by 2.3%, retail trade, transport and hotel & catering by 1.7%, real estate by 2.5%, financial and insurance activities by 5.3%, professional activities by 1.2%, and public administration and others by 0.4%.

Service sector distribution in 2014 | Millions of euros | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Retail, transport and hospitality sector | 232.124 | 32% |

| Public Administration, healthcare and education | 179.466 | 25% |

| Real Estate | 117.319 | 16% |

| Professional activities | 71.407 | 10% |

| Artistic and recreational activities and other services | 41.980 | 6% |

| Information and communication | 38.534 | 6% |

| Finances and insurance activities | 37.481 | 5% |

Source: Ministry of Economy and Competitivity.

Construction Sector

The main indicators for the construction sector slowed their decline significantly. Housing investment at current prices fell by 3% in 2014, compared with a drop of 14.3% in 2013.

Most of the more recent economic indicators also show a growth trend. In 2014, the Construction Industry Output Index (IPIC) closed with an average increase of 17.4%, 16 points higher than in 2013. The apparent consumption of cement (seasonally adjusted) gathered pace in January to an annual increase of 9.6% (7.9% in December). As a result, it closed 2014 with a slightly positive growth rate of 0.1%, after seven years of consecutive falls. The latest Labour Force Survey (Spanish acronym: EPA) data show that employment in the construction sector declined by 3.5% in 2014, compared with a fall of 11.4% in 2013 and 17.3% in 2012. However, there was growth of 4% in the fourth quarter in the number of people employed in the sector.

Foreign Trade

According to the Department of Customs and Excise, Spanish goods exports remained strong in 2014, with year-on-year growth of 5.5% and a value of 240.03 billion euros, a new high in the current historical series beginning in 1971.

Imports rose by 5.7% year-on-year to 264.51 billion euros.

The moderate increase in exports, together with the stronger increase in imports, led to a worsening of the Spanish trade balance in 2014 to 24.47 billion euros. It should be noted that 2013 and 2014 were years with the two best trade balances relative to GDP since records began, at -1.6% and -2.3% respectively.

The non-energy balance, according to the classification by sector of the State Secretariat for Trade posted a surplus of 13.6 billion euros, compared with a surplus of 25.04 billion in 2013 (provisional data), while the energy deficit fell by 7.1% year-on-year to 38.07 billion euros.

Finally, the coverage rate, which measures the ratio of exports to imports, stood at 90.7%, 2.9 percentage points lower than in 2013 (provisional data), but better than the annual coverage rate of the historical series, except for 2013 when there an all-time high (93.4 with definitive data) was recorded.

By region, in 2014 non-EU exports now account for 36.6% of the total. Growth was particularly strong in Spanish exports to North America (22%) and Asia, excluding the Middle East (16.3%). In terms of the proportion represented by the main geographical areas that are destinations for our exports, 63.4% went to the EU (49.7% to the Eurozone), 9.5% to Asia as a whole (3.1% to the Middle East), 6.8% to Africa, 5.8% to Latin America and 5% to North America.

| Foreign Trade: breakdown by sectors (January-December 2014) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | EXPORTS | IMPORTS | ||||

| % total | var.14/13* | contrib.** | % total | var. 14/13* | contrib.** | |

| Food, drinks and tobacco | 15,5 | 4,4 | 0,7 | 10,7 | 3,0 | 0,3 |

| Energy related products | 7,2 | 7,1 | 0,5 | 20,9 | -3,1 | -0,7 |

| Raw materials | 2,4 | -2,9 | -0,1 | 3,6 | 0,0 | 0,0 |

| Intermediate goods (non-chemical) | 10,7 | 1,2 | 0,1 | 6,8 | 5,1 | 0,3 |

| Chemical goods | 14,2 | 2,9 | 0,4 | 15,0 | 3,9 | 0,6 |

| Capital goods | 20,1 | -0,5 | -0,1 | 17,8 | 9,5 | 1,6 |

| Cars | 14,8 | 6,2 | 0,9 | 11,6 | 19,4 | 2,0 |

| Consumer durable goods | 1,4 | -4,1 | -0,1 | 2,4 | 13,0 | 0,3 |

| Consumer goods | 9,2 | 7,8 | 0,7 | 11,0 | 13,2 | 1,3 |

| Other goods | 4,4 | -11,0 | -0,6 | 0,3 | -25.0 | -0,1 |

| TOTAL | 100,0 | 2,5 | 2,5 | 100,0 | 5,7 | 5,7 |

* A efectos de cálculo de variación interanual, la comparación se hará con los datos provisionales de 2013. ** contrib.: contribución a la tasa de variación de las exportaciones/importaciones totales, en puntos porcentuales. Fuente: S.G. de Evaluación de Instrumentos de Política Comercial de la Secretaría de Estado de Comercio del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, a partir de datos del Departamento de Aduanas e II.EE. de la Agencia Tributaria

The foreign sector has been playing an increasingly important role due to its positive contribution to GDP growth in recent years: 1.5% in 2008, 2.8% in 2009, 0.9% in 2010, 2.2% in 2011 (ESA 1995), 2.3% in 2012 and 1.4% in 2013 (ESA 2010). This has offset somewhat the negative situation of domestic demand. According to the National Statistics Institute, the contribution of net exports to GDP in 2014 was negative (-0.8 points) although is expected to be slightly positive (0.2 points) in 2015.

According to the latest data from ICEX [the Spanish export and investment institute], in 2014 the number of exporting companies in Spain was 147,731, 2.2% down on the figure in 2013. However, it is worth noting the significant growth in companies that have decided to become international, 35.1% up on the figure in 2010. More important still is the increase in the number of companies that export on a regular basis (45,481 companies in 2014) with growth of 10.5% on 2013.

The most important sectors for our exports are within the range of medium and high technology, totalling 54.5% of our goods exports. Specifically, capital goods are the main export sector, at 20.1% of the total, although they fell by a year-on-year 0.5% in 2014. The automotive sector (14.8% of the total) rose by 6.2% and chemicals (14.2% of the total) by 2.9% year-on-year. The sub-sectors with the largest contribution to export growth in 2014 were cars and motorcycles (0.9% points), other food (0.4 points), gas (0.4 points) and clothing (0.3 points).

Foreign Investment: foreign direct investment in Spain

According to data from January to September 2014 in the Foreign Investment Registry of the State Secretariat for Trade of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Competition, which includes the main component of direct investment flows, i.e. investment in any form of shares in capital, foreign investment in Spain lost ground so far in 2014 after a recovery in 2013. In fact, total gross investment fell by 20.4% to 10.69 billion euros, while net investment fell by 16.2% to 8.07 billion euros. On a positive note, foreign divestment also fell by 31.2%. In fact, divestment by foreign companies in our country fell from 3.81 billion euros in the first nine months of 2013 to 2.63 billion euros in the same period of 2014.

| Foreign direct investment in Spain | January-September 2014 (millions of euros) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | % Change 14/13 | ||||

| Gross Inv. | Net Inv. | Gross Inv. | Net Inv. | ||

| Total investment in shareholdings | 10.691 | 8.066 | -20,4 | -16.2 | |

| Investment not including ETVEs* | 9.756 | 8.466 | -4,5 | 24,6 | |

| In unlisted companies | 9.563 | 8.469 | -6.1 | 20,3 | |

| In listed companies | 192 | -3 | 615,7 | 99,0 | |

| Investment by ETVEs | 935 | -401 | -71,0 | -114,2 | |

*ETVE - Empresas de Tenencia de Valores Extranjeros (Foreign Securities Holding Companies). Source: Registro de Inversiones Exteriores.

Discounting investment in Foreign Securities Holding Companies (Spanish acronym: ETVE), the resulting investment or productive investment, which is the investment impact on the real economy, was 91.25% of total investment of 9.76 billion euros. Of this amount, direct gross investment channelled into listed companies has been very low, at only 192 million euros in the first three quarters of 2014 (direct investment is considered to be only investment which accounts for 10% or more of the company's share capital and voting rights). At the same time, gross productive investment in unlisted companies amounted to 9.56 billion euros (down 6.1%), while net productive investment has performed well at 8.47 billion euros, up 20.3% on the same period last year.

The first three quarters show an improvement in all components of foreign investment in year-on-year terms, given how they performed in the first half of the year.

Foreign Investment: Spanish direct investment abroad

According to the Foreign Investment Registry, in the period January to September 2014, total Spanish gross investment in shares in the capital of foreign companies amounted to 10.26 billion euros, a fall of 31.3%, while net investment (not including Spanish disinvestment abroad) was 2.05 billion euros, down 79.2% on the first nine months of 2013. The main reason for these results was investment by ETVEs, with 898 million euros of gross investment (down 83.8%) and 773 million euros of net investment (down 117%).

| Spanish direct investment abroad | January-September 2014 (millions of euros) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | % Change 14/13 | ||||

| Gross Inv. | Net Inv. | Gross Inv. | Net Inv. | ||

| Total investment in shareholdings | 10.263 | 2.047 | -31,3 | -79,2 | |

| Investment not including ETVEs* | 9.365 | 2.819 | -0,2 | -46,9 | |

| In unlisted companies | 8.563 | 6.435 | 1,3 | 37,5 | |

In listed companies | 829 | -3.615 | -13,3 | -669,8 | |

| Investment by ETVEs | 898 | -773 | -83,8 | -117,1 | |

*ETVE - Empresas de Tenencia de Valores Extranjeros (Foreign Securities Holding Companies). Source: Registro de Inversiones Exteriores.

The most positive aspect of this period corresponds to productive investment (not including ETVEs), at 9.37 billion euros, 91% of total gross investment. Although the figure fell by 0.2%, due to the bad performance of listed companies (down 13%), investment in unlisted companies posted weak growth of 1.3% on the same period in 2013. Net productive investment fell by 46.9% overall, due to the effect of liquidations of listed companies, while net investment in unlisted companies grew by 37.5% on the same period last year.

Agreements for Mutual Promotion and Protection of Investments (Spanish acronym: APPRI)

The Agreements for Mutual Promotion and Protection of Investments are bilateral mutual agreements that contain measures and clauses designed to protect investments made by investors of each country party to the agreement in the territory of the other party under international law.

Following the Treaty of Lisbon, the European Union became exclusively responsible for foreign direct investment, as part of common trade policy. As an initial consequence, on 7 July 2010, the Commission adopted a Communication on a comprehensive European policy on international investment and a proposed Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing transitional arrangements for bilateral investment agreements between Member States and third countries, which was finally approved by the European Parliament and of the Council as Regulation 1219/2012, of 12 December 2012, and entered into force 9 January 2013.

The basic aim of the Regulation is to guarantee legal certainty and maintain the level of protection of foreign investments of Member States, allowing not only the survival of the current APPRIs but even the negotiation and entry into force of new agreements with the prior authorisation of the European Commission. Today, Spain has 72 APPRIs in force, mainly signed with non-OECD countries, covering 25% of Spanish investment abroad.

Retail trade in Spain: the background and current situation

In 2012, the latest year for which figures are available, the gross value added (GVA) of the retail trade sector accounted for 12.4% of the total GVA at base prices of the Spanish economy, up from the year 2000 when the sector only accounted for 11.1%, mainly due to more moderate growth in other sectors such as industry and the primary sector. In 2012, retail trade accounted for 44.5% of GVA at basic prices of the trade sector, with wholesale trade at 42.3% and vehicle trade at 13.2%.

| Retail Index (constant prices) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year/Month | January | April | July | October | Yearly average |

| 2010 | 103,89 | 95,50 | 109,32 | 99,51 | 100,00 |

| 2011 | 99,07 | 93,47 | 102,56 | 92,47 | 94,22 |

| 2012 | 95,53 | 82,86 | 94,70 | 84,02 | 87,61 |

| 2013 | 87,20 | 80,77 | 93,06 | 83,64 | 84,15 |

| 2014 | 86,95 | 80,83 | 92,92 | 85,26 | 84,91 |

Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística

The trend in retail sales has followed the economy as a whole. From a peak in 2007, the General Retail Trade Index recorded six consecutive years of declines at constant prices, until 2013. However, there are signs of a turnaround in the second quarter of 2013, since, following falls of more than 10% in annual growth rates in February and March 2013, growth entered positive territory towards the end of the year, except for December, which was stable. In 2014, annual growth rates were positive in seven of the 12 months, including the last four months of the year, and over the year the annual rate grew for the first time since 2007.

The number of premises in the trade sector increased from 913,256 in the year 2000 to 922,502 in 2014, with a peak in 2008 at over one million, according to the INE. This increase is due to the increase in wholesale trade premises, since in this period the number of retail trade premises declined slightly, from 617,305 in 2000 to 583,908 in 2014. The total number of retail trade outlets fell by 1.4% between 2013 and 2014 (8,264 fewer).

| Number of premises | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total economy | Total trade | Vehicles | Wholesale trade | Retail trade |

| 2010 | 3.694.262 | 956.829 | 87.554 | 251.727 | 617.548 |

| 2011 | 3.655.457 | 943.665 | 83.654 | 253.880 | 606.131 |

| 2012 | 3.606.241 | 937.266 | 82.438 | 254.233 | 600.595 |

| 2013 | 3.554.925 | 929.300 | 83.170 | 253.958 | 592.172 |

| 2014 | 3.527.412 | 922.502 | 83.916 | 254.678 | 583.908 |

Source: Directorio Central de Empresas of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística

In the economy as a whole, the figures for the number of companies in the period 2000-2014 are positive, with a net increase of 523,918 companies. However, in trade there has been a decline of 11.2% since 2000 (59,333 fewer).

On the employment front, the number of people employed in the trade sector increased by 15.4% between 2000 and 2014, from 2,483,800 in 2000 to 2,866,750 in 2014 (annual average), or 382,950 more according to the Labour Force Survey of the National Statistics Institute. The number of jobs in the fourth quarter of 2014 was higher, 2,892,500, thanks to increases in employment in the last two quarters.

In retail trade, the number of jobs increased by 17.3% between 2000 and 2014, from 1,559,000 to 1,875,275 (annual average), or 316,275 more. The increase in the number of people employed in retail trade in the period 2000-2014 was general across most autonomous regions.

In the fourth quarter of 2014, the unemployment rate in the trade sector was 9.4%, which compares with the unemployment rate of 23.7% in the economy as a whole.

- Retail trade: unemployment rate of 9.4%.

- Wholesale trade: unemployment rate of 10.5%.

- Vehicle trade: unemployment rate of 7%.

Female employment accounted for 44.2% of total employment in the retail sector in 2000 and 57.6% in retail trade (36.7% in the total economy). In the fourth quarter of 2014, these percentages increased to 50.1% and 61.8% respectively (45.6% of the total economy).

According to the annual survey by the National Statistics Institute on the Use of information and communication technologies and e-commerce in businesses, the percentage of companies in the trade sector with computers is very high, at 99.6% in January 2014. The percentage of companies in the retail sector with Internet access and a website/webpage stood at 73.8% in January 2014.

| Number of companies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total economy | Total trade | Vehicles | Wholesale trade | Retail trade |

| 2010 | 3.291.263 | 796.815 | 73.915 | 217.295 | 505.605 |

| 2011 | 3.250.576 | 782.194 | 69.729 | 219.466 | 492.999 |

| 2012 | 3.199.617 | 773.657 | 68.425 | 219.245 | 485.987 |

| 2013 | 3.146.570 | 765.379 | 69.096 | 218.820 | 477.463 |

| 2014 | 3.119.310 | 758.483 | 69.728 | 218.938 | 469.817 |

Source: Directorio Central de Empresas of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística

According to the results of the Business Innovation Survey organised by the National Statistics Institute, the percentage of companies in the trade sector with innovative activities has declined over the past four years, to 6.6% of the total. The proportion in the overall economy is much higher (16.1%).

In 2012, at the beginning of this term of office, the economic crisis that began in 2008 continued to produce a strong contraction in consumption, affecting retail trade, and in particular small traditional shops. This situation began to change in late 2013 and 2014, when trade indicators began to improve steadily. The latest Bank of Spain report with economic forecasts for the Spanish economy, published in December 2014, puts GDP growth in 2014 at 1.4% and in 2015 at 2%. Household consumption is expected to grow by 2.3% in 2014 and 2.6% in 2015.

All indicators are showing signs of recovery. For example, registered unemployment in retail trade fell in December 2014 on the same month in 2013 by 4.6% (18,571 fewer unemployed). It is important to note that retail trade has recorded 13 consecutive year-on-year falls in registered unemployment (year-on-year declines every month since December 2013). In month-on-month terms, unemployment fell by 13,985 (down 3.5%) in retail trade as a result of the Christmas season. Compared with other Decembers since 2009, the monthly fall in the number of unemployed in retail trade is the second biggest after 2013.

Similarly, the retail trade confidence indicator for Spain, prepared by the European Commission, stood at a 10.5 points in January 2015, a positive value for the fourteenth consecutive month (since December 2013), following on from continuous negative values since April 2004, and an increase of 0.5 points on the previous month.

Research, development and innovation

There is a broad consensus on the importance of science, technology and innovation in economic development. Spain's science, technology and innovation policy is based on the 1986 Common Law on Scientific and Technological Research Coordination and Support (Ley 13/1986), since repealed. The profound changes witnessed over the past thirty years have led to the adoption of a new legal and regulatory framework: the Common Law on Science, Technology and Innovation (Ley 14/2011).

The Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation System comprises a set of institutions that are classified according to their function under the Common Law on Science, Technology and Innovation into three areas: policy coordination and definition; support for research, development and innovation, and implementation.

Coordination of R&D&I policies

(Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas y Medioambientales)The law provides for a new model of governance for the Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation System that acknowledges the pivotal role of the autonomous communities in the development of regional R&D&I systems - particularly in innovation - coupled with the coordination of Central Government in scientific research. The coordination of R&D&I policies is reflected in the overall goals shared by all public authorities. The Spanish Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation (2013-2020) is the instrument and multiannual reference framework for R&D&I policies in Spain. It is intended to serve both for the development of science and technology research and innovation plans and of research strategies for the smart specialization of the various public authorities.

(Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas y Medioambientales)The law provides for a new model of governance for the Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation System that acknowledges the pivotal role of the autonomous communities in the development of regional R&D&I systems - particularly in innovation - coupled with the coordination of Central Government in scientific research. The coordination of R&D&I policies is reflected in the overall goals shared by all public authorities. The Spanish Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation (2013-2020) is the instrument and multiannual reference framework for R&D&I policies in Spain. It is intended to serve both for the development of science and technology research and innovation plans and of research strategies for the smart specialization of the various public authorities.

One of the chief aims of the Strategy is to address one of the major deficits in the Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation System: the failure to transfer knowledge. The aim is to transform R&D&I from a concept divided into research, development and innovation into an inclusive idea, a complete trajectory that begins with the generation of an idea and ends with its marketing. Hence, there are no longer two strategies and two plans as before, but rather a single strategy and a single plan that address research and innovation without distinction.

State promotion of R&D+I

Science, technology and innovation policy and the definition of the chief promotional instruments of R&D&I in Central Government are the responsibility of the Secretariat of State for Research, Development and Innovation of the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, to which the Public Research Agencies report. These agencies are charged with direct implementation of the bulk of the country's scientific and technological research.

The Centre for Technological and Industrial Development and the new State Agency for Research (to be created under the Common Law on Science, Technology and Innovation and attached to the Ministry of Research, Development and Innovation) are the two funding agencies for Central Government R&D&I activity. They are also responsible for the management of actions under the State Plan for Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation (2013-2016) approved by the Council of Ministers at its meeting on 1 February 2013, and the processes of selection, evaluation and monitoring of these actions and their results and impact.

Gran Telescopio Canarias (Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias)Also reporting directly to the State Secretariat is Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology, which performs the important task of the social diffusion and promotion of science and technology and delivers advanced services to the science and technology community.

Gran Telescopio Canarias (Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias)Also reporting directly to the State Secretariat is Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology, which performs the important task of the social diffusion and promotion of science and technology and delivers advanced services to the science and technology community.

Implementation of R&D&I activities

Scientific and technological research and innovation activities are implemented by a large number of agents who form an integral part of the system.

The main agents in carrying out research in the State sector are the Public Research Institutions, which, besides being important centres for the implementation of scientific and technical research activities, also provide scientific and technological services and advice.

The Public Research Institutions reporting to the Ministryof Research, Development and Innovation are:

- Spanish Council for Scientific Research (CSIC), amultidisciplinary and multi-sector agency;

- National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIA), whichspecializes in agricultural and agritechnology research;

- Spanish Oceanography Institute (IEO), which specializesin oceanographic research and fishery resources;

- Geological and Mining Institute of Spain (IGME),which focuses on research in this field;

- Centre for Energy and Environmental Research (CIEMAT), which engages in energy and environmental research;

- Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands (IAC),which specializes in astrophysics research;

- Carlos III Health Institute (ISCIII), which coordinates research activities in the field of healthcare and assists with knowledge transfer to the National Health System.

The Public Research Institutions are joined in the implementation of R&D&I by public universities, which collaborate closely within their research groups and through the creation of joint centres, mainly the CSIC-University.

Besides universities, public research institutions, health centres and business, which are responsible for the bulk of Spain's R&D, research centres attached to the autonomous communities, Central Government or both currently play a prominent role.

The Spanish scientific system has a number of organizations that act as supporting elements. These include:

- Technology platforms, which involve all players intending to move research, development and innovation forward in a specific sector (businesses, technology centres, universities, etc).

- Technology centres, non-profit entities that undertake research, development and innovation projects in partnership with business. They are often described as intermediators between public research and the productive sector.

- Science and technology parks have enjoyed public support in the form of various calls for proposals and are presently one of the actors involved in the institutional cooperation between Central Government and the autonomous communities.

- Unique Science and Technology Facilities (ICTS) are centres that are unique in their own field, for which public promotion and financing are justified by their high investment and maintenance costs or by their unique or strategic nature. They include the Antarctic Bases, the Almeria Solar Platform, the Barcelona ALBA Synchrotron, the Canary Islands Telescope, and the Iris Network of advanced electronic services for the scientific community. In addition to the ICTS set up across national territory, Spain participates in major international facilities such as the European Particle Physics Laboratory (CERN), the experimental reactor ITER, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), the Laue-Langevin Institute (ILL) and the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (ISIS), among others.

Main results from research, development and innovation in Spain

The figures from R&D+i show how the resources allocated to research in Spain have grown considerably in recent years. Total spending on R&D activities stood at 1.24% of Gross Domestic Product in 2013, whereas this figure stood at 0.43% of GDP in 1981. Spending by the private sector accounts for 0.66% of GDP, which is significantly less than the 1.3% spent on average by companies throughout the European Union. In turn, private funding of R&D activities accounts for 53%. This constitutes one of the main deficits in the Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation System as regards the more advanced countries in Spain's peer group where corporate funding accounts for an average of 65% of total spending on R&D. In fact, the European Union states that the private sector must contribute two-thirds of all funding in order to produce a healthy R&D+i system. Increasing participation from the private sector, both in terms of funding and the execution of R&D+i activities, is therefore one of the main challenges faced by the Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy.

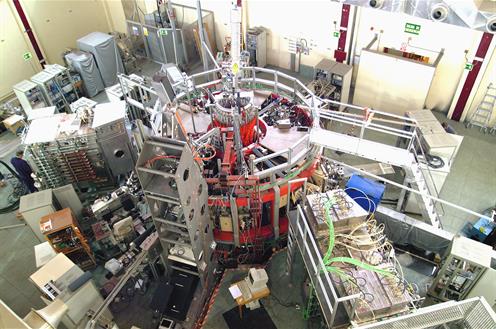

Proyecto TJII (Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas y Medioambientales)The number of researchers (Full-time Equivalent (FTE)) in Spain stood at 123,583 in 2013, an increase of over 50% since 2001. This upward trend is also reflected in the percentage of employees dedicated to R&D activities (FTE), which accounted for 1.2% of the total workforce in 2012 compared with 1.17% in the EU-27.

Proyecto TJII (Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas y Medioambientales)The number of researchers (Full-time Equivalent (FTE)) in Spain stood at 123,583 in 2013, an increase of over 50% since 2001. This upward trend is also reflected in the percentage of employees dedicated to R&D activities (FTE), which accounted for 1.2% of the total workforce in 2012 compared with 1.17% in the EU-27.

The scientific weight of Spain has increased in recent years and the country now stands as the tenth country in the world in terms of scientific production (eighth when considering publications in those magazines of greatest impact), with a growing percentage of articles included in the top 10% of most quoted publications in the world.

However, and although Spain remains below the European average, the number of Spanish patents has increased significantly in relative terms. This, together with the previously-mentioned low proportion of corporate spending on R&D, is preventing greater development of innovative capabilities within the productive fabric overall.

Between 2000 and 2012, international cooperation increased significantly and this is reflected in such indicators as the number of scientific articles published under co-authorship, which rose from 27.2% to 41.4%, or the number of patent applications made under partnership.

Particular mention should be made of the degree of participation in the European Research Council (ERC) actions of excellence, which in the period 2008-2013 issued 82 "Advanced Grants", 112 "Starting Grants" and 20 "Consolidator Grants" (there has only been one round of the latter, in 2013) to researchers undertaking their work in Spain, which guarantees the progress made in terms of the quality of Spanish research centres.

The 2013-2020 Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy

The Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy (2013-2020) was approved on 2 February 2013 as one of the instruments for "fostering economic growth and competitiveness in the country". This Spanish strategy steers R&D+i policies towards the creation of capabilities and, above all, the production of results.

The aims of the Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy are:

- To recognize and promote R&D&I talent and employability.

- To support scientific and technological research, attaining a standard of excellence.

- To support business leadership in research, development and innovation.

- To foster research, development and innovation activities targeting society's overarching challenges and, in particular, those affecting Spanish society.

The deployment of the Spanish Science and Technology and Innovation Strategy also provides for a set of cross-cutting measures laying the foundations for our work. The horizontal pillars are:

- The definition of an environment favouring the development of R&D&I.

- Boosting specialization and aggregation in knowledge generation.

- Fostering the transfer and management of knowledge and the search for long-term commitment in public/private R&D&I partnerships.

- Support for internationalization and promotion of international leadership.

- The definition of a highly competitive territorial framework based on the "smart specialization of the territories".

- The dissemination of scientific culture.

Vista aérea del Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad)Central Government's National Scientific, Technological and Innovation Plan for 2013-2016 develops and funds the actions contained in the Spanish Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy.

The 2013-2016 National Scientific, Technological and Innovation Research Plan is the basic public funding instrument for R&D&I. It acts, therefore, as a road map for monitoring future developments in this field. It is addressed to all agents in the Spanish Science System responsible for: a) implementation of R&D&I; b) management of R&D&I, and c) delivery of R&D&I services for progress in science, technology and innovation in Spanish economy and society overall.

The specific aims of the National Plan include:

- Improving the training and employment of human resources in R&D&I.

- Improving the standard of scientific and technical research.

- Strengthening the international leadership and capacity of institutions that implement scientific and technical research.

- Promoting access to scientific and technological infrastructure and scientific equipment.

- Supporting business leadership in R&D&I.

- Encouraging the creation and growth of technology-based companies and the promotion of efficient investor networks.

- Fostering collaboration in R&D&I between the public sector and the business sector.

- Incentivizing R&D&I oriented to meet the challenges of society.

- Fostering the internationalization of the R&D&I of agents of the Spanish Science System and their active participation in the European Research Area.

- Increasing the scientific, technological and innovative culture of Spanish society.

- Making progress in demand-based R&D&I policies.

Thus, the actions of Central Government included in the National Plan are divided into four state programmes in line with the objectives of the Strategy. The 2013-2016 National Plan, whose specific actions are set out in annual action plans, is structured as follows:

- National Programme for the Promotion of Talent and Employability, formed by three sub-programmes: Training, Recruitment and Mobility.

- State Programme for the Promotion of Scientific and Technical Research Excellence, composed of four sub-programmes: Knowledge Generation, Development of Emerging Technologies, Institutional Reinforcement, and Scientific and Technical Infrastructure and Equipment.

- National Programme for Business Leadership in R&D&I, with three sub-programmes: Business R&D&I, Key Enabling Technologies and collaborative R&D&I oriented towards productive demands.

- National Programme for R&D&I Oriented to Societal Challenges, organized around eight major challenges: health, food safety and quality, energy, transport, climate change, economy and digital society and security and defence.